We were standing by a large turquoise pond, utterly alone and hundreds of kilometres deep in the heart of the Mackenzie Mountains on the border between the Yukon and the Northwest Territories. Ahead lay 60 kilometres of non-stop rapids, three hikes, and 557 kilometres of wild South Nahanni waters to paddle.

The buzz of mosquitoes gradually drowned out the noisy engine of our floatplane as it disappeared past the striking sharp grey peak of Mt. Wilson and down the dark green valleys of black spruce. We had finally arrived at Moose Ponds, headwaters of the South Nahanni River. I gazed over to the large questionable patch of plastic peeling off the bottom of the pale red rental canoe as large drops of rain drummed off the scattered air-tight blue plastic equipment barrels. The first thing that came to mind was, I sure hope we brought enough toilet paper.

It’s not that I was in any particular need to relieve myself when I mused aloud to my wife Marilyn but that I was still in an auto-pilot planning mode that comes with being head organizer and guide of a three-week mid-July paddling trip with Marilyn and her two brothers who were meeting us a week down river.

This adventure had to be extra carefully planned not only because it was a lengthy and remote one, but the trip of a lifetime for Preben and Jan, and their first real canoe trip. If something happened to my brothers-in-law their wives would make sure I never paddled again.

With that said, it took more than a year to organize, starting with coordinating the cheapest and most efficient way to fly us and our gear to the river and back to Toronto. That required four different aircraft companies and was, by far, the biggest chunk of the trip’s cost. Then I had to figure out our food, clothing and equipment needs, which would be key to our happiness, and possibly survival, out on the river.

In the process, I had created a stack of lists thicker than the Bible that need constant refinement as I took stock of how much food and other supplies we used up on other canoe trips and tested clothing and equipment. All this was done with the knowledge that everything had to fit into eight 60-litre waterproof barrels, which is why I spent a lot of time doing things like roaming store aisles for the perfect eating plates that could also act as bowls, and inspecting an assortment of tents I bought and set up in my basement to determine which one would make the cut and which ones went back to the store.

After all I had been through, I was going to need a little time to unwind, especially after the hectic morning in Fort Simpson, the little village in the NWT where Marilyn and I met our pilot Jacques at the floatplane base.

“We’re flying out as soon as possible,” he announced. “I’m not flying in the afternoon. It’s too dangerous. The hot weather is going to increase the chance of storms the longer we wait.”

We didn’t argue. The the two-and-a-half hour flight had already seemed a little sketchy since we were travelling as far as the Cessna could possibly go. Every last drop of fuel was needed to get us there and Jacques back.

Thankfully, Chris, the floatplane company owner, lent us his truck and we immediately jumped in and raced around the village doing last-minute errands like picking up stove fuel, registering with the park, and finding paddles to replace ours which the baggage handlers hadn’t loaded on our flight from Toronto the day before.

With the hectic morning and the distant threatening storm clouds we passed on flight behind us, the true test of my organizing and guiding abilities was about to begin as we paddled through the “Ponds” and down the constantly growing river. I couldn’t afford to relax quite yet, since we would soon hit the 60-kilometre long stretch of rock-strewn whitewater that could easily wreck a canoe, and at 15C, kept our food nice and cold on the bottom of the boat, but could also bring on hypothermia in no time if we dumped. Only a handful of paddlers try this very technically demanding section each year so there wouldn’t be much help upriver. Not only that but, since this section lies outside the Nahanni Park boundary, we would be responsible for the huge bill incurred if we had to call search and rescue officials for help on our satellite phone.

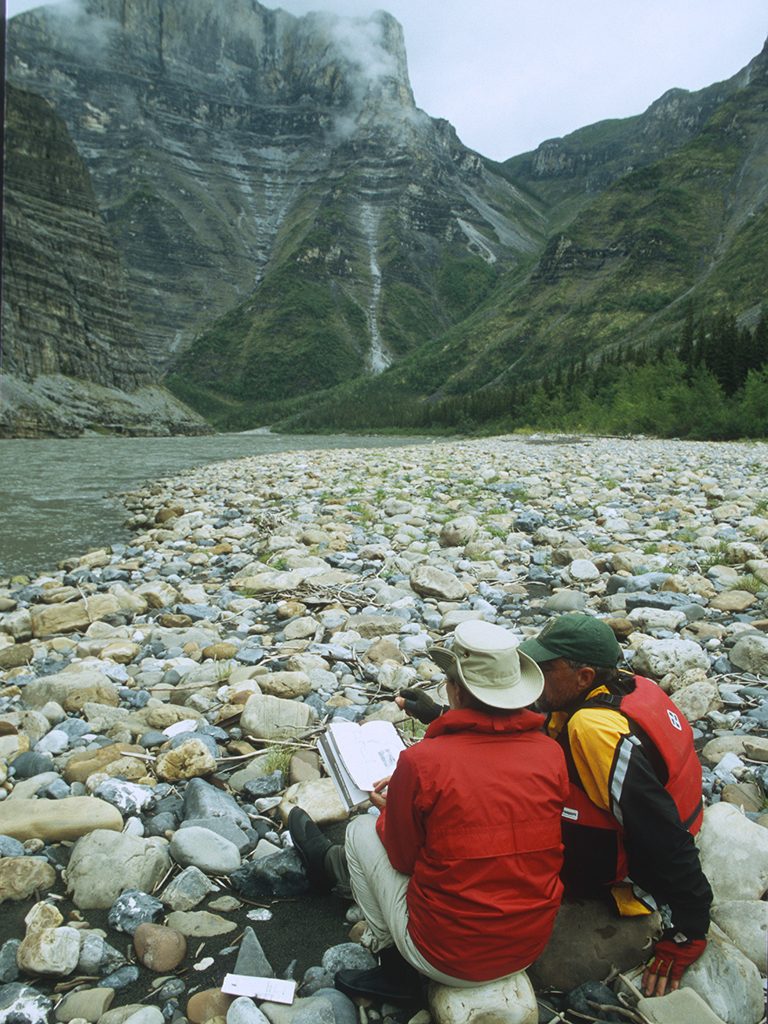

Around what corner the major whitewater would be, we didn’t know since we hadn’t a clue where we were for the first couple of days no thanks to our laminated topographical maps that were too large scale to be useful and the vague maps in the guide book. But once we hit it, Marilyn and I flew through two days of wild turbulence, dodging and sneaking around bleached boulders on the rushing clear cold water, often barely able to catch our breathe. It was some of the best whitewater we had paddled together but I was also relieved when it was over.

During that first week, our attention also focused on re-hydrating meals into something that resembled food. Marilyn and I had spent hours and hours at home cooking, dehydrating, portioning, and tossing zip-locked meals into the freezer as our kids looked on in horror with comments such as, “that looks disgusting” and “that’s why we’re not going on the trip.”

During that first week, our attention also focused on re-hydrating meals into something that resembled food. Marilyn and I had spent hours and hours at home cooking, dehydrating, portioning, and tossing zip-locked meals into the freezer as our kids looked on in horror with comments such as, “that looks disgusting” and “that’s why we’re not going on the trip.”

It was an experiment in convenience since most people dehydrate ingredients and make the meals at camp or eat store-bought meals. Lucky for Jan and Preben, we had mastered the technique by the time we met up with them at Rabbitkettle Lake just inside the park boundary. Fill the baggy of peanut brittle-like substance with water in the morning and by dinner at 9 p.m., presto, a beautiful metamorphosis. We all looked so forward to eating every day that our conversations almost always centered on food. No soul searching or deep philosophical discussions on our trip. It was more like, “what appetizer shall we have with the chicken pesto” followed by “what’s on for tomorrow night?”

The first full day the four of us were together proved to be the worst day of the trip. Our rather heavy plastic container of Grand Marnier fell from a bear cache and exploded on the ground. After that heart-stopping incident, we had to improvise and our daily after-dinner ritual became coffee and a splash of Bailey’s, which seriously depleted our large store of coffee. Eventually, we were down to one cup each in the morning, which doesn’t sit well if you a) are from Ontario and b) relax around the campsite until 1 p.m. every day.

Despite the unfortunate mishap, everyone was still in high spirits even when the day-time temperature dropped from 24C to 6C overnight. One day, we awoke to find the surrounding mountains capped with fresh snow and a wind that drove the cold right into our spines. It was a smart move to pack winter hats and gloves and Marilyn’s excellent idea of filling our neoprene socks and boots with warm water before pulling them on was a truly memorable feeling.

Despite the unfortunate mishap, everyone was still in high spirits even when the day-time temperature dropped from 24C to 6C overnight. One day, we awoke to find the surrounding mountains capped with fresh snow and a wind that drove the cold right into our spines. It was a smart move to pack winter hats and gloves and Marilyn’s excellent idea of filling our neoprene socks and boots with warm water before pulling them on was a truly memorable feeling.

As the swift water turned a muddy brown and pushed us quickly to new campsites among staggering cliffs and mountains, we began to see that the books had not only been right about the extremely variable temperatures but how quickly a sunny day can turn nasty.

In the mountains, rain clouds are always lurking somewhere just out of sight, so I made sure the tarp was always within easy reach and the first thing to put up when we set up camp. Tarping soon became an art for Jan and I. We would sometimes spend hours refining its positioning, using ropes, bungee cords, paddles, dead branches, and duct tape to produce the perfect set-up so that the tarp hung high enough and close enough to the fire pit without going up in smoke.

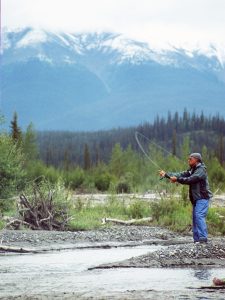

After the chores were done, our free time would largely consist of gazing at the incredible scenery around us, searching the ground for neat looking rocks, writing in our journals, and picking blueberries and raspberries for the next morning’s breakfast. Even the Frisbee I had stashed away as a surprise for some summer beach fun flew only once. It got more use as a plate, cutting board, fire fan, and to help hold up the tarp. The fishing rods didn’t get used a whole lot either and the four novels I hauled around? I read a total of three paragraphs.

After the chores were done, our free time would largely consist of gazing at the incredible scenery around us, searching the ground for neat looking rocks, writing in our journals, and picking blueberries and raspberries for the next morning’s breakfast. Even the Frisbee I had stashed away as a surprise for some summer beach fun flew only once. It got more use as a plate, cutting board, fire fan, and to help hold up the tarp. The fishing rods didn’t get used a whole lot either and the four novels I hauled around? I read a total of three paragraphs.

God knows, we tried to use everything we brought since it took a lot of effort to pack everything into the those barrels. But even after scrutinizing every item before it made the final “to go” list, there were many other items we never really used but are still a requirement for most canoe trips.

Tent stakes didn’t do much good for most of our campsites since the best spots were on open beaches of stones and rocks. I did have the foresight to tie loops of shock cord around the tent loops to secure large rocks to in case of a strong wind. And the four new headlamps also could have stayed at home since total darkness never really comes in the summer that far north.

You would think that bug repellent is also a must and we brought plenty of that – 10 small bottles, yet we only really needed it once when we discovered that the entire mosquito and black fly population of the NWT congregates in Nahanni Butte, a little community near the end of the river where we made the unfortunate decision to camp.

Thankfully, the bear spray stayed in their holsters the whole time. The closest we came to encountering large fur-covered animals occurred when a young moose wandered into our campsite one morning. Another time, a moose, this one reeking so foul it woke Marilyn up, unloaded a huge mound between the tents while we were sleeping. We also got within spitting distance of a huge, lazy bison but no need for pepper spray there, either. I was tempted to spray a shot of the cayenne pepper mixture in our chili to help justify the hefty $65 each we paid to rent four bottles in Fort Simpson.

Thankfully, the bear spray stayed in their holsters the whole time. The closest we came to encountering large fur-covered animals occurred when a young moose wandered into our campsite one morning. Another time, a moose, this one reeking so foul it woke Marilyn up, unloaded a huge mound between the tents while we were sleeping. We also got within spitting distance of a huge, lazy bison but no need for pepper spray there, either. I was tempted to spray a shot of the cayenne pepper mixture in our chili to help justify the hefty $65 each we paid to rent four bottles in Fort Simpson.

Over time, everyone in our group grew accustomed to life out on the river. With no one around and not a care in the world (except for the ongoing chance encounter with a bear), the stress of city life quickly subsided. All of us fell into a state of blissful meditation. So, when we reached the campground at the famous Virginia Falls, culture shock hit us hard. Boardwalks ran like roads in the forest among dozens of brightly coloured tents.

People were all over the place. I was aghast even though I knew beforehand that the spot would be a bottleneck for visitors. Floatplanes and helicopters came and went like it was an airport, carrying fuel and wardens up and down river or dropping people off for a day at the falls. The spot is also a popular starting point for a week’s trip down the most breathtaking section of the river that features four deep canyons and enough other geological and geographical wonders to make it a World Heritage Site.

As the group’s guide, it was my job to make sure we had enough of the solitude we had been seeking for the duration of the trip. So, during our stay, I stealthily gathered enough information from the warden and other campers to determine the best day to head out without having a large group of paddlers just ahead of or behind us.

As the group’s guide, it was my job to make sure we had enough of the solitude we had been seeking for the duration of the trip. So, during our stay, I stealthily gathered enough information from the warden and other campers to determine the best day to head out without having a large group of paddlers just ahead of or behind us.

In the process, I discovered that people are just as gossipy this far out in the wilderness as in a small town. Rumours flew down the river faster than the current. A discussion with another paddler would usually go something like this;

“Have you seen the couple who brought their kids down from the Little Nahanni River?” “That’s some pretty big whitewater to take kids on.” “Heard they hooked up with some Latvian filmmakers.” “I think I saw them upriver. Are they using a raft or canoes?” “Both. I heard they don’t have filming rights.” “No way.”

The grandest story on the river that we heard involved a group of five Americans who were paddling in tiny solo inflatable rafts. Each member could only carry a single small duffel bag. Incredible since not only were they paddling for a month but packed climbing equipment to explore the world famous Cirque of the Unclimbables along the way. Word was that their main food source was guzzling olive oil.

Two days later we happily slipped away from the tent city and after the kilometre-long portage, met only two other people at the foot of the falls whose rafting party wasn’t leaving until the next day. Our escape was a success.

All we had to do now was make it through the canyon just ahead. This was the one spot on the river Preben and Jan were nervous about and the reason I had taken them out several times before the trip to practise their whitewater paddling skills. No chance to portage here or scout the river, either. The only guidance I could give them was to keep the canoe pointed downstream – the rest was up to them.

We pushed off in the cold rain. The current immediately grabbed the canoes and we sped around the bend between the dark rock walls while waves the size of ocean swells tossed us like toys. Marilyn and I fought hard to keep the canoe from going broadside until we made it out of the torrent and then we watched as Preben and Jan followed into calmer waters, beaming with smiles and eyes lit with excitement.

I was relieved, once again, that we all had made it through without a mishap as we continued through the towering canyon landscape, gawking upwards in constant amazement so much our necks seized up. I felt even better when we reached Hell’s Gate, a mysterious piece of the Nahanni that boils up like a witch’s cauldron, that Jan and Preben wisely decided to portage after we met up with the Americans and watched as the last one dumped his raft. Turns out the rumours we heard about them at the falls had been true.

The last few days on the river were more relaxing with no more menacing rapids to worry about. At Prairie Creek in the pouring rain, a vast and flat treeless area of narrow creeks and mineral deposits where animals and paddlers like to congregate, we met the godfather of guides, Neil Hartling who was the first person to run guided trips on the Nahanni, and co-author of the guide book we were using on our adventure. He had his hands full with a rafting trip loaded with members of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, hoping to convince them to put effort into expanding the park’s boundary.

Wanting to be neighbourly, we had intended to bring over a plate of capers and cheese on crackers until we heard the group discussing the five sauces available to them for the night’s dinner as they stood under a huge canopy sipping liqueurs around two large tables decked with checkered table clothes. The rest of their gear was scattered all over the beach like they were having a giant yard sale. We were sure they weren’t hard done by.

The next afternoon, we paddled through the last of the canyons, fighting with the still speedy current to go as slowly as possible. We wanted to take in as much of the scenery as we could, knowing we may never be on another magical mystery tour of the Nahanni.

The terrain quickly flattened out soon after and the river branched out into many channels, aggressively eroding the riverbanks and sending trees crashing to the water. My only concerns now were the strong and unfriendly currents and the remote chance of one of us getting hit by a falling tree. Jan and Preben not only got caught in a small whirlpool but were within a couple of metres of getting pummeled by a tree by the time we navigated through the maze.

It wasn’t until the last afternoon on the river after a lunch that included Preben getting sucked down above the knees in quicksand that I could finally hang my guiding hat up and thank Mother Nature for not putting us through too many tests. All that work organizing the trip has paid off. Were we safe, on schedule, and having the time of our lives. And we didn’t run out of toilet paper after all.

Story by Ralph Plath

Photos by Ralph Plath

and Marilyn Mikkelsen

Unforgettable Journey

Getting there and Back

You can fly from Ottawa to Edmonton with several different airlines. To get from Edmonton to Yellowknife book a flight with Canadian North. To get from Yellowknife to Fort Simpson, you can take a flight with Buffalo Air or Air Tindi. Floatplane charters are available from other communities. But Fort Simpson is the most popular since the Nahanni National Park headquarters are there.

Charter floatplane companies include:

Simpson Air

– website – http:/www.simpsonair.ca

– tel: 1 866 995 2505

– email – info@simpsonair.ca

South Nahanni Airways

+1 (867) 695-2263

If You Go on Your Own

Recommended books are Nahanni River Guide by Peter Jowett and Neil Hartling (a guidebook) and Dangerous River by R.M. Patterson (a historical book)

Nahanni National Park Reserve:

– website – http://www.pc.gc.ca

Equipment rentals are available from the river outfitters listed below:

Taking a Guided Trip

River outfitters include:

Nahanni River Adventures

– website – http:/www.nahanni.com

– tel. – 1-800-297-6927

Blackfeather Wilderness

– website – http:/www.blackfeather.com

tel: (888) 849-7668 toll free email: info@blackfeather.com

Nahanni Wilderness Adventures Ltd.

– website – http:/www.nahanniwild.com

– tel. – 1-888-897-5223 (Can/US)

or 001-403-688-7238 (Int’l) email: info@nahanniwild.com